“The term ‘African art’ can be quite limiting.”

Collector Interview | Joseph Awuah-Darko

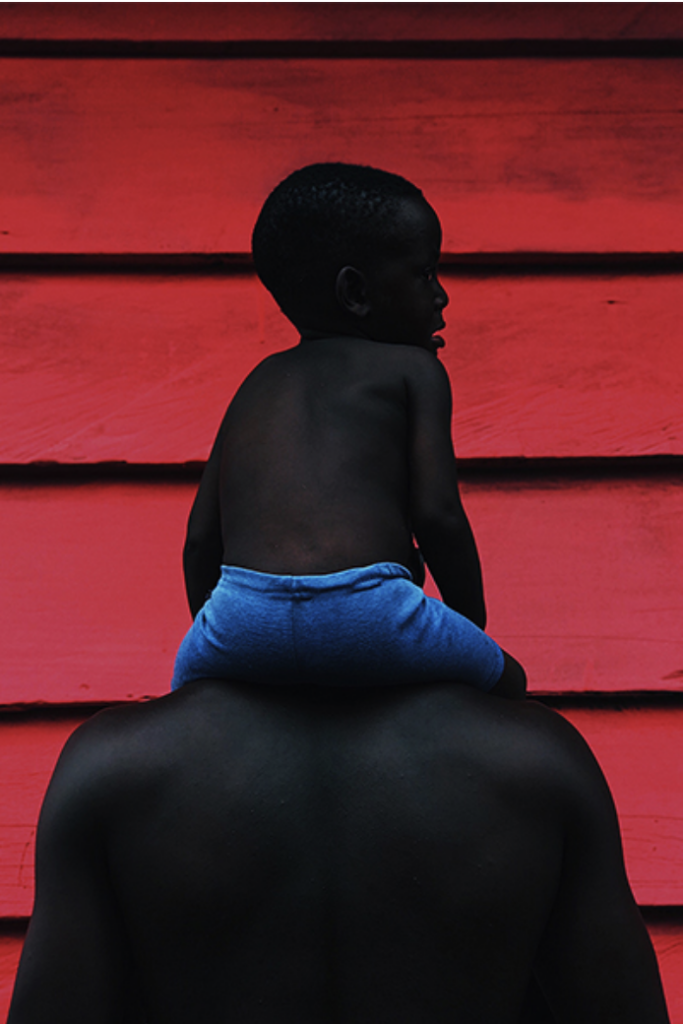

How to introduce a creative multi-talent in a single paragraph? Joseph Awuah-Darko, born in London, has lived in Ghana since the age of five. There, the artist, collector, and philanthropist has established a successful residency program and supports young African artists wherever he can. viennacontemporaryMag discussed the urgency to diversify the global art world and how to win over the next generation of collectors with the 26-year-old prodigy.

viennacontemporary: Joseph, you have been ranked as Forbes 30 under 30 many years ago, you are an environmental activist, artist, and have now built up your own artist residency and museum programs in Ghana – how can one person do this all?

Joseph Awuah-Darko: I’d say, I had many lives. I started my journey as a musician when I was 19, much younger, that was just sort of championing alternative music in Ghana. It was a very short period, maybe a year and a half, but it went really well, and then I focused more on academia and did my tenure at Ashesi University. I worked with the World Bank Climate Innovation center and the Ford Foundation and studied environmental degradation at was then dubbed the largest electronic waste dumpsite in Ghana. I did empirical and ethnographic research about the harmful cancerogenes that came from the burning of copper wires and the circular economy that existed in e-waste dumpsites.

And then you moved on, from the dumpsite to artworld…

That was actually my first segway into art: I upcycled electronic waste in a sort of at Duchamp-ian manner at my first exhibition at Gallery 1957 in Ghana in 2019. I had always been a collector and involved in art but that was my first-time creating art. But before that I had just organic relationships with emerging artists like Gideon Appah.

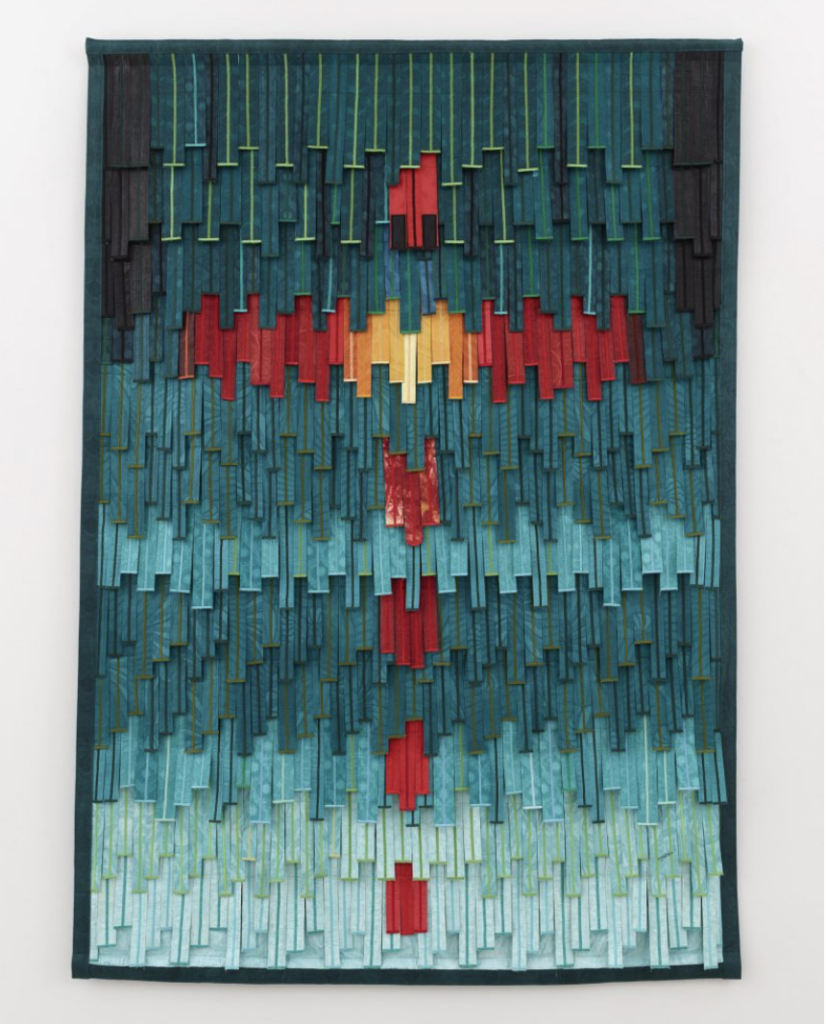

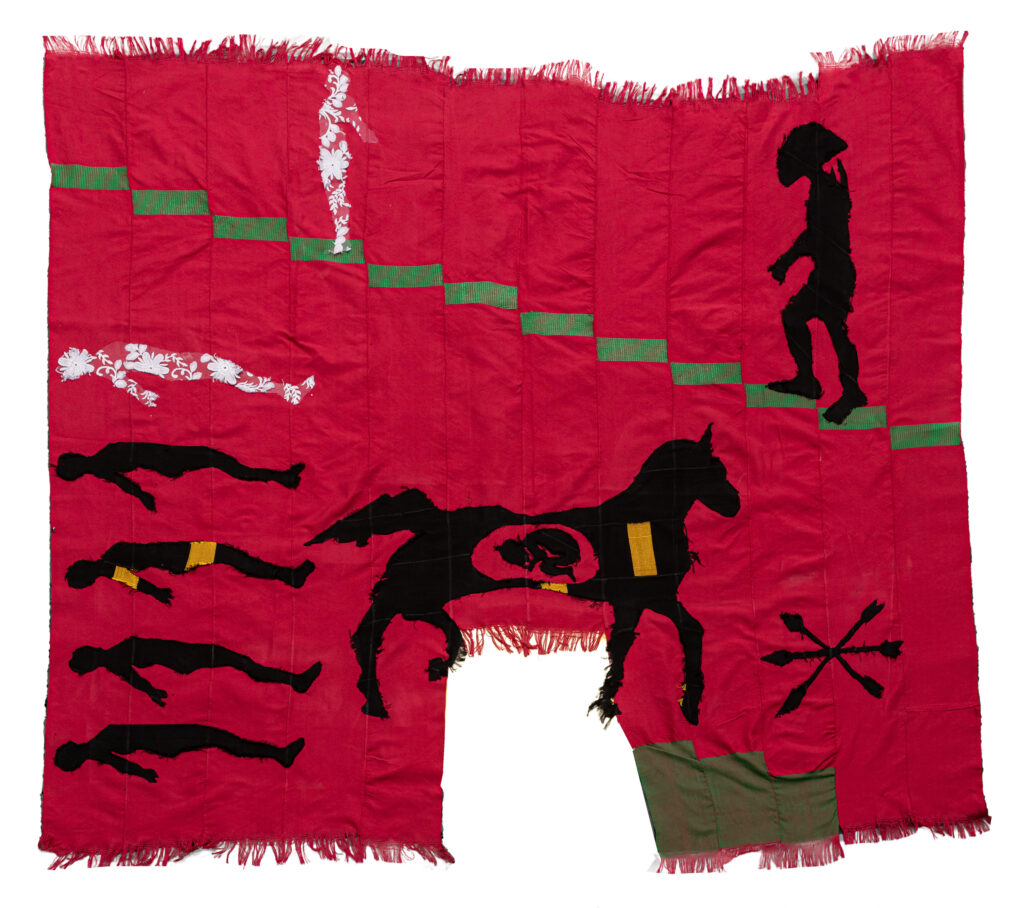

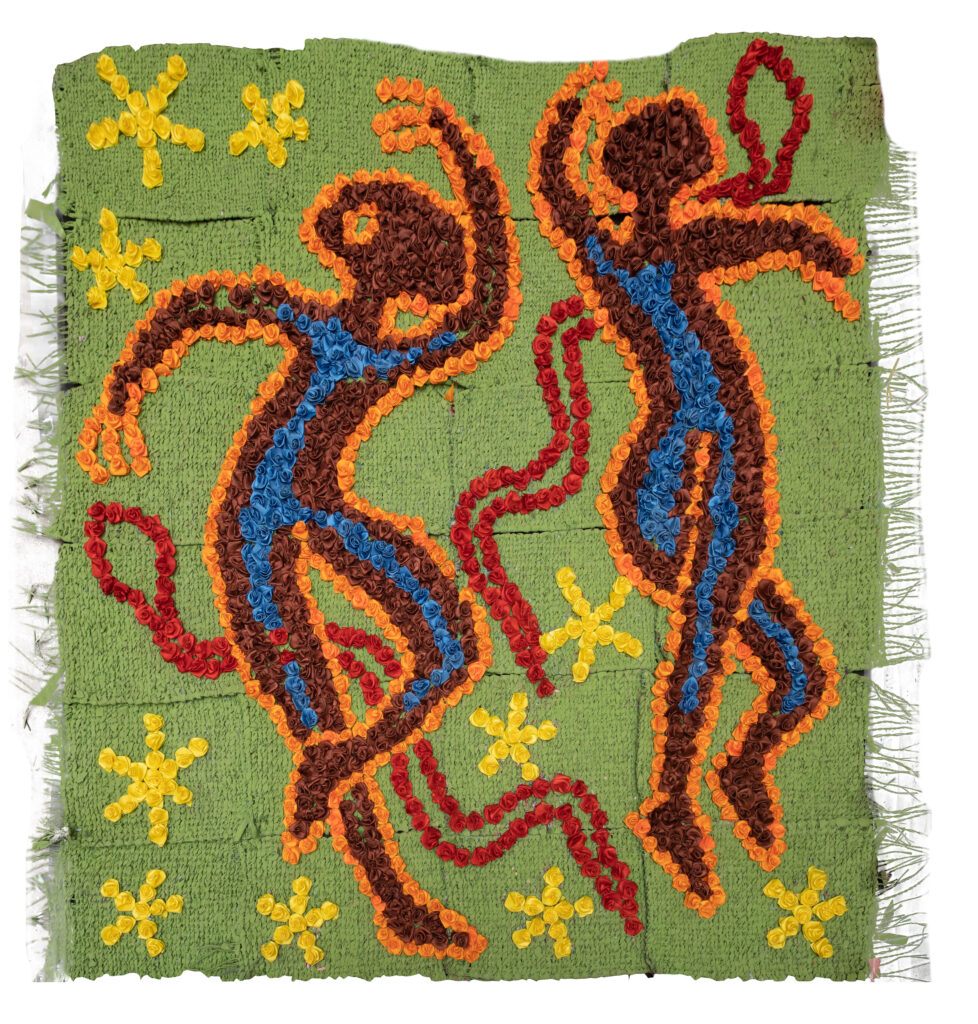

Joseph Awuah-Darko, Piloso Courtship, 2022 (200cm x 190cm) 78.74 in x 74.80 in. Courtesy of Joseph Awuah-Darko.

So, out of these friendships you started collecting?

Yes, I had these friendships with these brilliant artists early on in their careers, and I believed my contemporary eye for artists who I knew would have a bright future. For me it was about just being inspired by the fact that there were artists working within a subculture and being part of a wider contemporary art discussion. I thought it was important to be involved in supporting artists as a collector, beyond being a custodian of works that had a store value and growth potential. So that was sort of the early stages but also lots of studio visits – secret studio visits as I call them, were in huge parts responsible for my collecting at an early point because I went to so many artists’ studios over a period and that’s how these friendships were formed.

What place does collecting have in your life? What do you look for?

Collecting is my life. I really have a passion for emerging artists who are trying to create distinction within their voices. One artist that really excites me is Maku Azu, a Ghanaian diasporan artist who lived in Thailand with her husband before moving back to Ghana. For me, collecting is about investing in an artist’s story, it’s sort of the process from the inception point of feeling forward and experimenting to the point where they hopefully experience their first gallery show. Some artists who have been part of the residency program feature in my private collection which was recently captured on Larry’s List.

Your residency program the Noldor Residency, located in Accra in a hip arts district called South Labadi, aims to support emerging contemporary artists from the diaspora and the continent. How do you select the participants?

It is not limited to artists living and working on the continent but is also open to artists who have a desire to return for a tenure at the institution. I have this hearty obsession of being part of their story as a custodian. Things I look out for are gender parity, the gallery programs they are a part of. Also, in terms of longevity, I look at whether they are living on the continent or within the diaspora, whether they have a more academic background or are self-taught autodidacts. Altogether, it must resonate with the information I have and that of the selection committee’s, in sort of having artists that truly have something unique to say across all disciplines – whether it’s ceramics, sculpture, tapestry, or painting.

Last year we had 265 applicants in total and we only selected nine. So, it’s a competitive program, which I guess is a happy problem! We have enjoyed that, and it has just been very organic to see that interest snowball and grow.

How do you see the development of African art in the Western art market?

I am very careful to make sure when discussing African art, we are talking about art by artists who happen to come from Africa. Otherwise, the term can be quite limiting. I have friends who are British or Asian collectors, who say, “Obviously I am collecting contemporary art, but I haven’t heard of African contemporary art!” and I am like “It’s the same!” I have a bit of an ambivalence about the ghettoization of African art. It is a subcategory in its contextual relevance, but I don’t think African art is inferior to larger discussions on contemporary art.

Do you find that African contemporary art is being put more into the global discussion?

Definitely. We do have artists who are diasporan or of African origin like Gideon Appah or Joy Labinjo showing at Frieze, like Emmanuel Taku showing in Brussels with Maruani Mercier last year…You do have this normalization of African contemporary art, and when I say “African contemporary art”, I mean emerging artists showing in these global art fairs in a very valid and co-equal capacity to their contemporaries from Germany or Mexico, or other parts of the world. There is a huge buyers’ market in Nigeria where you also have a really great art fair ART X Lagos run by my friend Tokini Peterside-Schwebig.

What do you think about the 1-54 art fair, the international fair dedicated to contemporary African art?

What they did when they started in 1-54 Marrakech was so small and sweet and intimate – now it has grown into this multi-jurisdictional behemoth with fairs in London and New York. It is great that they are efforts to shine a unique light in considering the arguable novelty of African contemporary art as a global phenomenon. I am very good friends with Hannah O’Leary who is the Head of Modern and Contemporary African Art at Sotheby’s and we have always asked this ironic question “does there even need to be an African contemporary art department? Isn’t it part of the wider contemporary sale discussion?” My answer is: Given that there was incongruence in the understanding of African contemporary art in the beginning, I think fairs like 1-54 are important because they are a lot of collectors’ introductory points to a relatively nascent market and so I think they do matter – also in ensuring that there is an increase in black-owned and African galleries represented at the fair.

Mind you, art is as much about the cultural producers as it is about artists.

It is true, the discussion mostly circles around artists, not so much around gallerists.

It is crucial that art fairs like 1-54 fight for an increasing focus on the need to have gallerists from the continent featured in their shows. I read an interesting article that said unfortunately the demographic of gallerists showing at the 1-54, especially in London, is skewed – there seems to be an imbalance of African and non-African gallerists. Part of the elements that gallerists look out for in an art fair they participate in, especially when that fair projects the championing of African contemporary art producers is that very balance. I know that art fairs are essentially a business, and this may come into play when filling the booths, however, it’s just a sense of understanding the need to contribute to encouraging more diversity.

Another challenge the established art market faces is an aging clientele, and to establish a next generation of collectors. What is your take on that?

The art world has been accused, from a collectors’ point of view, of being very exclusive. But a lot of major gallerists, who are also my friends, whether it’s Adora Mba, who runs ADA \ Contemporary in Ghana, Ron Mandos of Galerie Ron Mandos in Amsterdam, or even Simon Lee who has a lovely space in London. They all expressed a preference for collectors who have an existing history of building great collections – more out of fear of flippers as opposed to an elitist point of view. I think it’s because you are worried that a collector who is more of a novice will be more likely to compromise your artist’s market by placing it in a secondary market thoughtlessly (laughs) whereas somebody who is more of a seasoned, ranked collector would not. But most gallerists are typically concerned about you whether the collectors understand the responsibility of being a custodian. And that is the difference.

So, what are your tips for attracting young collectors?

Be passionate about what it means to vet collectors, understand that when you are supporting an artist, be it emerging or mid-career, it’s about building a collector base and a community and not collectors in isolation. Another piece of advice I would give to galleries – obviously very unsolicited (laughs) – is to not be afraid of challenging themselves to really understand that just because a collector is young doesn’t mean that they lack vision. Don’t write off a collector that easily – there are some impressive Asian collectors in South Korea who are very discerning in their taste and how they see themselves building collections. And also, to diversify the means through which you vet collectors. As we learned from COVID, the discovery of art through Instagram skyrocketed. And that does approach a largely younger demographic, people between 20 and mid-40, and so at the end of the day you have to understand that there is nothing wrong with collectors who come through social media, just be as passionate in engaging with them as you are in vetting them.

Do you still make art?

I am quietly creating tapestry of my own. In fact, one of my works is entering the Stanley Museum of Arts’ permanent collection and I just participated in an amazing textile-based group show with Mindy Solomon Gallery in Miami.

It’s amazing how much you have accomplished! What are your upcoming plans?

It’s crucial for me to continue to create a team to grow a residency program that supports artists. Noldor is doing what it’s supposed to do, which is supporting local and diasporan-emerging artists and taking them to the next level. I hope it keeps doing that with longevity. We have expanded within the Institute Museum of Ghana and we had our second museum exhibition this year with Samuel Olayombo – a member of Noldor’s alumni. It has been great to produce these exhibitions, obviously, there is a linear connection from the residency to the museum program. There is a lot of room still. We have the Enlighten Program, where we invite students from the local municipality, and in the three months since launching, we had 160 students come to visit the space. For me, seeing even more kids at the institution would be great.